From Eureka Alert, Source: AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEPHROLOGY

Study reveals long-term effectiveness of therapy for common cause of kidney failure

Highlights

Among individuals with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, those who were treated with tolvaptan for up to 11 years had a slower rate of kidney function decline compared with historical controls.

Annualized kidney function decline rates of tolvaptan-treated patients did not change during follow-up.

Washington, DC (July 19, 2018) -- New research provides support for the long-term efficacy of a drug used to treat in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), a common cause of kidney failure. The findings appear in an upcoming issue of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (CJASN).

The hormone vasopressin promotes the progression of ADPKD, the fourth leading cause of end stage kidney disease. In the three-year TEMPO 3:4 and in the one-year REPRISE phase 3 clinical trials, tolvaptan (a vasopressin receptor antagonist) slowed the decline of kidney function in patients with ADPKD at early and later stages of chronic kidney disease, respectively. The results suggest that tolvaptan might delay the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation, provided that its effect on kidney function decline is sustained and cumulative over time, beyond the relatively short duration of TEMPO 3:4 and REPRISE. Because all patients participating in these clinical trials were given the opportunity of continuing tolvaptan in an open-label extension study, investigators have now gathered information on the long-term efficacy of tolvaptan.

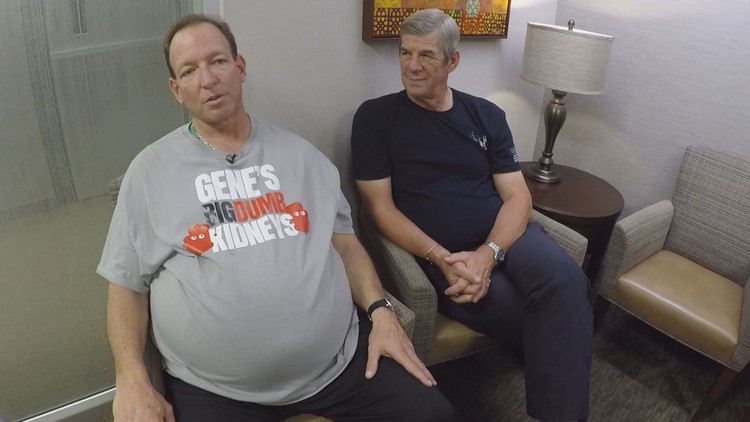

A team led by Vicente Torres, MD, PhD (Mayo Clinic) retrospectively analyzed information on 97 ADPKD patients treated with tolvaptan for up to 11 years at the Mayo Clinic. Kidney function was measured as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

The investigators found that patients treated with tolvaptan had lower eGFR slopes compared with controls (-1.97 vs -3.50 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year) and a lower risk of a 33% reduction in eGFR from baseline. Also, the annualized eGFR slopes of patients treated with tolvaptan did not change with the duration of follow-up. The team also compared the eGFR values observed at the last follow-up in the tolvaptan treated patients to the anticipated last follow-up eGFR values, estimated using a previously validated predictive equation. Differences between observed and predicted eGFRs at last follow-up increased with duration of treatment, suggesting that the beneficial effect of tolvaptan on the eGFR accumulates over time.

"The results of the study suggest that the effect of tolvaptan on eGFR in patients with ADPKD is sustained, cumulative, and consistent with potentially delaying the need of kidney replacement," said Dr. Torres.

PKD Foundation

From PKD Foundation

PKD Connect: a new online resource for anyone impacted by polycystic kidney disease

When you connect, you won’t face PKD alone.

Whether you are looking for information or empathy, PKD Connect is a great starting point. Nowhere else will you discover so many ways to connect with other patients, families and caregivers who know exactly what you’re going through because they’ve been through it themselves. At PKD Connect, these programs and resources mean no one faces PKD alone:

Peer Mentor Program

PKD Hope Line

Online Community

Disease Management Resources

PKD Foundation Research Update

PKD Research Grants

This year, we are awarding 15 research grants to outstanding PKD scientists through our Research Grant Program. We will spend more than $2 million over the next two years on these projects.

The awardees represent top researchers and physician scientists in the field. And included in this list is our first-ever Australian grantee! We are proud to collaborate with the PKD Foundation of Australia to co-fund this grant and are committed to our global alliance to grow PKD research to find more treatments. Meet our grants recipients at pkdcure.org/grants.

PKD Fellowships

In addition to our grants, we have also selected two young researchers as recipients of our PKD Foundation Fellowships. These fellowships recognize early-career scientists whose initial achievements and potential identify them as rising stars in the PKD field. This program is key to bringing in the next generation of scientists who are critical to the future of PKD research. Each fellow will receive $60,000 a year for two years, totaling nearly a quarter of a million dollars. Meet our fellows at pkdcure.org/fellowships.

Thanks to your support, these investments will propel critical research to deepen our understanding of the genetic and pathological processes involved in PKD and accelerate the development of more treatments for PKD patients.

Thanks again for all you do to support our mission and make a difference in the lives of everyone impacted by PKD.

Sincerely,

David Baron, Ph.D.

Chief Scientific Officer

Dialysis Issues

Proposed Ohio Constitution amendment would restrict kidney dialysis centers

A proposed constitutional amendment that would restrict profits and increase regulations at Ohio outpatient dialysis centers is one step closer to getting on November’s ballot, pending certification of enough valid signatures to qualify.

The Kidney Dialysis Patient Protection Amendment is backed by Ohioans for Kidney Dialysis Patient Protection, an offshoot of a similar initiative California voters will consider in November. Supporters say it provides necessary regulations to a highly profitable industry, while opponents warn it would threaten patient care and close treatment centers.

“We’re already very regulated. It’s redundant,” said Diane Wish, president of the Ohio Renal Association, the trade group representing the 326 outpatient dialysis clinics in the state. “If the goal is to make dialysis more affordable for patients it’s not doing it. It’s not going back to the patient.”

The proposal would cap revenue from treatment at 115 percent of “direct patient care services costs and all health care quality improvement costs.” Dialysis centers that charge beyond that would be required to provide rebates to insurers and would face fines for noncompliance.

It would also require the state to inspect kidney dialysis centers annually, reviewing compliance for processes such as handling and disposal of biohazardous waste, cleaning and maintenance of equipment, and adherence to patient-care plans.

The 349 Ohio Department of Health-licensed dialysis centers in the state are on a three-year schedule in line with federal guidelines, said J.C. Benton, state health department spokesman.

The pro-amendment group, backed by the Service Employees International Union, says it has turned in enough petition signatures to put the issue on the statewide ballot, which will be verified by the Ohio Secretary of State’s Office by July 24. At least 305,591 valid signatures are required.

Anthony Caldwell, spokesman for SEIU District 1199 and a member of the petitioner committee, said the amendment will address huge mark-ups dialysis centers charge patients with private insurance and strengthen safety and hygiene regulations.

“We feel like to have that kind of very acute care that you should have that done in the safest, cleanest environment possible,” Mr. Caldwell said, adding the amendment would ensure “the money they are charging is going to care for consumers [so it is] done in safe and sanitary conditions.”

Dialysis is a costly and time-consuming medical procedure used to treat patients with kidney failure, or end-stage renal disease. Patients typically visit such clinics three days a week for about four hours at a time to have their blood extracted, filtered, and returned to their body through a machine. In 2016, about 18,000 Ohioans were on dialysis, according to the Ohio Renal Association.

Both the Ohio and California issues are funded in large part by SEIU-United Healthcare Workers. A coalition of groups against the amendment, under the umbrella Ohioans Against the Reckless Dialysis Amendment, includes the Kidney Foundation of Ohio, Ohio Renal Association, and the Ohio State Medical Association.

Ms. Wish, also a registered nurse and chief executive officer of Centers for Dialysis Care, a chain of nonprofit dialysis providers in northeast Ohio, said proponents of the measure would like people to believe the dialysis industry has no regulation.

It’s something that “could not be any further from the truth,” she said, citing adherence to federal guidelines and state inspections.

By capping revenue, Ms. Wish said it doesn’t make it more affordable for dialysis patients, as rebates go back to the insurance companies.

About 90 percent of dialysis patients have Medicaid or Medicare, she said, both exempt in the proposed amendment. In targeting private insurance, it reduces necessary revenue to offset lower reimbursements from government payers, she said.

She warned the amendment could cause some centers to close or consolidate, especially in rural areas where patient volumes are lower.

“Patients will have to travel farther and transportation is very difficult,” she said, adding that increased travel makes missing treatments and adverse side effects requiring hospitalizations more likely. “It’s just not good for patients.”

Mr. Caldwell said a revenue cap would incentivize dialysis centers to invest money back into direct patient care, which could include increased staffing or other safeguards to improve conditions, rather than giving it to shareholders.

Dialysis centers charge private insurance “a 350-percent markup” from the actual cost of care, far more than government insurers who negotiate rates. That cost is passed on to all private insurance customers, he said.

Mr. Caldwell’s union, which also represents Ohio Department of Health surveyors responsible for inspecting dialysis clinics, said reports of unclean or unsafe conditions warrant this action.

The 2017 U.S. Renal Data System Annual Data Report shows nearly 500,000 Americans received dialysis treatments in 2015. That year, total Medicare spending for beneficiaries with kidney disease was nearly $100 billion, according to the report.

Sacramento resident Irma Menchaca left her home the morning of June 6, 2008, for kidney dialysis treatment at DaVita University Dialysis Center in Campus Commons. She had begun regular treatments five years earlier because of her end-stage renal disease.

She arrived at the clinic and reported no health complaints, and by 9:45 a.m., she started what should have been a 180-minute treatment. But at 10:40 a.m., Menchaca was found unresponsive. Emergency personnel tried to revive her, but the 57-year-old wife and mother was pronounced dead on site.

Jurors in the wrongful death case in Colorado brought by her family concluded her survivors should receive $127 million in damages.

Yet news of this wrongful death award might never have reverberated to California if the company and a powerful labor union weren’t locked in a high-stakes, multimillion-dollar battle for voter sentiment here.

SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West has poured more than $7.9 million so far into an effort to persuade California voters to approve a statewide proposition that would limit the amount of profits that kidney dialysis companies such as DaVita and Fresenius can keep. Those companies have countered, putting at least $7.2 million into the opposition effort. The measure, now known as Proposition 8, won’t be decided until the November election.

The union and its supporters say the companies are sacrificing quality of patient care and the cleanliness of facilities in pursuit of profits that will wow Wall Street. The companies and their supporters say the SEIU-UHW has been trying unsuccessfully to organize dialysis center workers for years and that their true goal in pushing Prop. 8 is to gain higher wages for potential union members.

The Menchacas’ civil case, however, lent new evidence to SEIU-UHW’s contention that Denver-based DaVita is putting financial interests ahead of patient care.

Filed in federal court in Colorado, the lawsuit lists cardiac arrest as the cause of Menchaca’s death, attributing it to DaVita’s failure to alert Menchaca or her kidney specialist to a change in the acid concentrate DaVita was using to filter waste from her blood, ensure a healthy pH balance and correct any electrolyte abnormalities.

The company saved millions of dollars by switching to a dry acid concentrate called GranuFlo, the lawsuit alleged, and it had been shown that this new formula could lead to a dangerous biochemical imbalance that triggers abnormal heart rhythms and cardiac arrest.

Fresenius, the maker of GranuFlo, had informed DaVita of these dangers as early as 2003, but the company neither informed its patients nor physicians of the risks, and it didn’t stop using the product, according to the suit. If physicians had known, the lawsuit continued, they could have told the clinic staff how to avoid complications.

In March 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recalled GranuFlo, saying that its use could result in cardiopulmonary arrest and death if prescriptions did not take into account acetate levels. The FDA took corrective action and required Fresenius to include a warning about the prescription problem.

“What did DaVita do to mitigate those risks? Nothing,” plaintiffs’ attorneys Robert Carey and Stuart Paynter wrote in a July 11 op-ed in The Denver Post. “It switched to GranuFlo without telling the treating doctors. ... The reason DaVita acted this way was clear: Treating doctors would have rebelled had they been told that DaVita was using GranuFlo just to save money, with no clinical benefit and, for patients like ours, a 600 percent to 800 percent increase in the risk of cardiac arrest, according to the evidence admitted.”

DaVita’s chief medical officer, Allen R. Nissenson, defended his company in another July op-ed: “Strikingly, this lawsuit centers not on the product itself, but on the way we communicated to caregivers about GranuFlo, a powdered product that has been used in tens of millions of dialysis treatments over 25 years, and continues to be used in tens of millions of treatments today. The verdict is shocking when you consider the actual facts and science in this case. Our teammates did the right things, in the right way, and we would do it again the same way in the future.”

Nissenson described early warnings about GranuFlo as unsubstantiated speculation and said DaVita scores highly on clinical outcomes according to key benchmarks set by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Jurors, however, connected DaVita’s actions with the deaths of Menchaca and two other people included in the lawsuit — Madera resident Gary Gene Saldana and Chicago-area resident Deborah Hardin, dealing a total judgment of $383.5 million against the company.

SEIU-UHW argues that DaVita and Fresenius have a virtual monopoly in California, owning 72 percent of the clinics in the state, and Prop. 8 is intended to force them to invest more of their profits into patient care.

The initiative requires clinics and their “governing entity” to issue refunds annually to patients or their payers if revenue exceeds 115 percent of the costs of direct patient care and health-care improvements, and it provides for fining clinics that don’t issue refunds within 210 days of the end of a company’s fiscal year.

Because the profit cap is over and above what’s spent on patient care, the union says, companies have no incentive to limit spending on wages, equipment or facilities.

Yahoo Finance reported that DaVita recorded net income of $663.6 million in 2017 and Fresenius $1.3 billion, plus Fresenius’ operating profit margin was 12.4 percent and DaVita’s about 15 percent last year.

The average operating margin for the S&P 500 companies was 11 percent in 2017, according to market analyst Chris Murphy.

“Rather than investing in patients and the workers, they’re sending it (profit) back to their shareholders, their investors,” said SEIU-UHW spokesman Sean Wherley, “and as a result, there is no on-the-ground accountability to both improve the quality of life for these patients and the conditions for them and the workers taking care of them every day.”

Dr. Bryan Wong, a kidney specialist and a medical director for both DaVita and Fresenius, said the company’s centers, especially in California, are highly regarded. Medicare and Medicaid evaluates dialysis clinics on hundreds of requirements, and California has more clinics with four- or five-star ratings than any other state, he said.

He said the SEIU-UHW is putting its campaign to increase wages for dialysis clinic workers ahead of the interests of the roughly 66,000 dialysis patients across the state.

Instead of improving services, he argued that the initiative would ultimately result in clinic closures, making it harder for patients to find one. It’s a challenge to manage, he said, in an industry in which 90 percent of the customers are covered by Medicare or Medi-Cal, programs that don’t cover the full cost of dialysis care.

Opponents of Prop. 8 hired former California legislative analyst Bill Hamm’s economic think tank the Berkeley Research Group to assess the measure’s financial impact, and the report projected that 83 percent of dialysis clinics wouldn’t be able to cover costs if the measure passes.

“No company, either independent or nonprofit, can operate under these conditions,” Wong said. “So what’s going to happen? Patient care is going to suffer.”