From DrugWatch, By Kristin Compton, Edited By Kevin Connolly

National dialysis provider DaVita Inc. was recently ordered to pay $383.5 million to the families of three patients who died after they were treated with a solution called GranuFlo.

A federal jury in Denver on June 27 sided with plaintiffs who lost family members after receiving the treatments at DaVita clinics.

The patients suffered cardiac arrests, according to a statement from Hagens Berman, a law firm representing the plaintiffs.

“DaVita ignored many red flags that preceded the loss of life of these three patients and many others,” lead trial attorney Rob Carey of Hagens Berman said in a statement.

DaVita Inc. pledged to appeal the verdicts issued in the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado.

“GranuFlo is an FDA-approved product that has been in continuous use for more than 25 years,” DaVita Inc. said in a statement. “The issues raised regarding its alleged negative clinical side effects have been debunked and nephrologists use it daily for their patients. The plaintiffs in this case did not even claim that the product itself was dangerous.”

Each family was awarded $125 million in punitive damages, and $1.5 million to $5 million in compensatory damages.

A federal jury in Denver on June 27 sided with plaintiffs who lost family members after receiving the treatments at DaVita clinics.

The patients suffered cardiac arrests, according to a statement from Hagens Berman, a law firm representing the plaintiffs.

“DaVita ignored many red flags that preceded the loss of life of these three patients and many others,” lead trial attorney Rob Carey of Hagens Berman said in a statement.

DaVita Inc. pledged to appeal the verdicts issued in the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado.

“GranuFlo is an FDA-approved product that has been in continuous use for more than 25 years,” DaVita Inc. said in a statement. “The issues raised regarding its alleged negative clinical side effects have been debunked and nephrologists use it daily for their patients. The plaintiffs in this case did not even claim that the product itself was dangerous.”

Each family was awarded $125 million in punitive damages, and $1.5 million to $5 million in compensatory damages.

DaVita Provides Services to Nearly 200,000 Patients

GranuFlo is the brand name of a solution given to patients to replace lost fluids and minerals while they are receiving dialysis. Dialysis involves using a machine to filter the blood of people whose kidneys can no longer perform that task.

DaVita Inc., a Fortune 500 company, is the parent of DaVita Kidney Care, a provider of services to patients with chronic kidney failure and end-stage renal disease.

DaVita Kidney Care operates or provides services at 2,539 outpatient dialysis centers in the United States serving nearly 200,000 patients. It also runs 241 outpatient dialysis centers in 10 countries outside the United States.

Dialysis Solution Linked to Alkalosis

DaVita administers dialysis to patients using products manufactured by Fresenius Medical Care.

Nearly 3,200 Fresenius GranuFlo/NaturaLyte dialysis product lawsuits are currently pending in a Massachusetts federal court. These products can cause toxic pH imbalances in patients resulting in alklosis.

Alkalosis is a serious condition in which the body contains too much base, or alkali. This is the opposite of acidosis – excess acid in the body fluids.

Complications of alkalosis include:

Arrhythmias – heart beating too fast, too slow or irregularly

Electrolyte imbalances

Loss of consciousness

Coma

Seizures

Severe trouble breathing

Death

In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a Class I drug recall — potential for serious health consequences or death — of GranuFlo. The agency noted the risk of alkalosis in patients exposed to the acetate-containing dialysis product. Lawsuits allege DaVita knew or should have known about the alleged dangers.

DaVita Inc. says its “first priority is the safety of our patients.”

Kidney Donations

From KARE11 TV, Rochester, MN, by Adrienne Broaddus

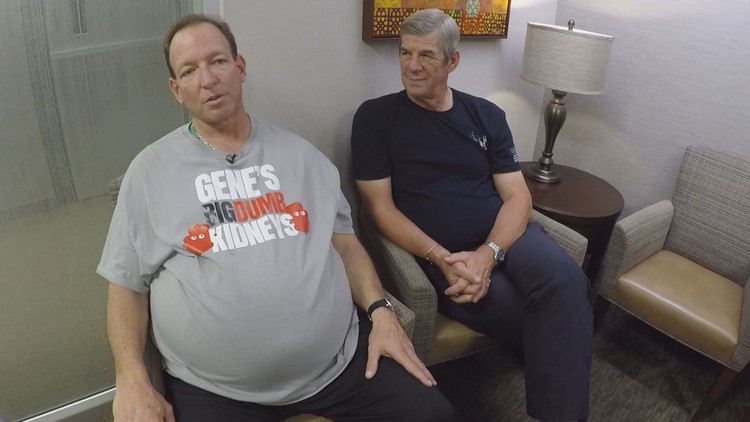

Champion. A title Gene Okun relishes.

Now, the man once-dubbed "Baby Arnold Schwarzenegger" holds a title he never wanted.

Doctors believe Okun, a former powerlifter and bodybuilder, has the largest kidneys in the world. An average kidney is the size of your fist. Okun’s are bigger than a football.

“I can’t say growing bigger kidneys was on my list of dream accomplishments. Unfortunately, as luck would have it, I am now famous for big kidneys and not bodybuilding,” he said.

Gene, who lives in Southern California, has genetic kidney disease. It’s called polycystic kidney disease, or PKD. The 50-pound dumbbells he used for training are the same weight as his kidneys.

PKD is a genetic disease passed from an affected parent to their child causing uncontrolled growth of cysts in the kidney. Most people with PKD experience kidney failure by age 60, according to the PKD Foundation.

The same disease Okun lives with ended the life of his father, also named Gene. For years, Okun, 52, tried to rewrite his story.

He launched an online campaign called Gene's Big Dumb Kidneys. Okun said he wanted to use comedy to raise awareness and search for a living kidney donor.

He calls the left one "Big". The right one is "Dumb". That’s how Okun describes his kidneys. Because of the disease, Gene never married or had children.

“That is a real traumatic thing as a child growing knowing you will need dialysis or transplant,” he said.

But Gene has a chance his father didn't. All thanks to his best friend, Bill McNeese. Most friends loan money and donate their time --- but an organ? In June, surgeons with the Mayo Clinic performed the lifesaving kidney transplant Gene needed.

Okun said he is “grateful for the blessing” of his living kidney donor.

“It became clear to me it was part of God's plan to do this, “McNeese said. “I am just a good friend. Somebody that does things without being asked because you care about somebody,” McNeese said. “It became clear to me it was part of God's plan to do this.”

Mayo Clinic's Dr. Mikel Prieto led the surgery. Initially, he thought it would take two hours, an hour for each kidney, but it took 12.

“His kidneys were enormous. Probably the biggest ones I have ever seen,” he said, “He is actually a thin guy. These enormous things inside his abdomen.”

Okun said he chose the Mayo Clinic because of a minimally invasive technique doctors used to laparoscopically remove the diseased kidneys. Because of it, Mayo surgeons can complete two procedures, with one surgery. According to its website, the Mayo Clinic pioneered the process of performing both kidney laparoscopic removal and transplant surgeries for polycystic kidney disease patients simultaneously. This procedure eliminates the need for two surgeries where the old kidneys would be removed first.

Living donation saves two lives: The recipient and the next one on the deceased organ waiting list. Kidney and liver patients who are able to receive a living donor transplant can receive the best quality organ much sooner, often in less than a year.

Following the surgery, Okun was able to see his feet. A sight he hadn’t seen in years.

“My stomach was flat. I could see my feet. Blown away I wasn't so round, anymore,” he said.

Gene and Bill, friends for 20 years, are now family for life.

“I am grateful for you saving my life. I truly wouldn't be in this spot if it wasn't for you stepping up and wanting to give me life,” Gene told Bill days after the surgery.

McNeese said he always wanted a brother. Now, he has one in Okun. Brother is a title Okun accepts with pride.

Five years ago, Sergio Cobos was just trying to stay alive. He had battled with kidney disease for years, and things were getting worse. His legs would fill with fluid and he was plagued by cramps. A previously athletic man of 36, he should have been in sound physical shape. But now he struggled to get up the stairs.

Then everything changed—he had a kidney transplant. Today, as he strolls out of a botanical glasshouse in a park by La Chopera, on the Manzanares river in Madrid, he seems healthy and relaxed, dressed in a bright tracksuit and trainers.

When Cobos’s doctor told him that his kidney disease had reached the point at which a transplant or ongoing dialysis was necessary, he asked his friends and family if any of them would offer him a kidney as a living donor. In all, 16 people said yes.

“My mum was meant to be donating for me and she was the most compatible one,” he says through a translator, “but suddenly within [the donor] list there was someone who was even more compatible.” He had been on the waiting list for just 20 days.

All he knows about the person who saved his life is that she was a woman from Madrid who was 10 years older than him and who died from a stroke. That a highly compatible deceased donor was available as well as so many willing living donors, including family members, is perhaps a reflection of something that makes Spain a very special country indeed: it leads the world in organ donation. And by quite a margin.

Figures published for 2017 reveal that 2,183 people in Spain became organ donors last year after they died. That’s 46.9 per million people in the population (pmp)—a standard way of measuring the rate of donation in a country.

Spain’s closest contender is Croatia, with 38.6 pmp (2016). It has maintained its position as the clear leader for the past 26 years. In a press release, Spain’s National Transplant Organization confidently describes the country as “imbatible”—unbeatable.

When attempting to explain Spain’s success, it’s the ‘opt-out’ (or presumed consent) system for deceased organ donation that is perhaps cited more often than anything else. Opt-out means that a patient is presumed to consent to organ donation even if they have never registered as a donor.

Countries that don’t have such a system often focus on changing the law as a key way to increase donations. Lawmakers in England are currently deciding whether the country should change from opt-in to opt-out like Spain. This is an attempt to redress a major difference between the UK and Spain: the rate of refusal of potential donors or their families in consenting to donation. The rate of family refusal is still significantly higher in England than Spain, at 37% versus 13%.

The tantalizing prize awaiting any country that does manage to increase donation rates is clear: better lives for potentially thousands of people. The impact Spain’s 2,183 deceased donors had last year, for example, is staggering. They made 5,260 transplant surgeries possible, including more than 3,200 kidney transplants and 1,200 liver transplants. There were 360 lung and 300 heart transplants. But would changing the law in countries that don’t have opt-out systems have the desired effect?

Working with families

In La Paz University Hospital, north of Madrid’s city center, Abderrazzak Lamjafar is sitting in a playroom. His 12-year-old daughter is nearby on the ward, having recently received a liver transplant. It’s nap time, so the playroom is deserted.

Lamjafar rests his hands on the little table in front of him. His daughter, he says, had originally been diagnosed in Morocco. “They said there was something wrong with her liver and that they are not experts and are not able to treat her there,” he says through a translator.

“They told me to take her home, get her to rest and eat well.” Some samples for medical tests were taken, but Lamjafar didn’t want to wait and see what might happen. Since his daughter had been born in Spain, she was entitled to treatment there. In Spain, doctors confirmed that she was suffering from acute hepatic failure—a type of liver dysfunction that can quickly put the patient into a coma if left untreated. When the disease occurs in children, transplantation is often essential.

After being referred from one hospital to another, they were eventually driven by ambulance from Murcia to La Paz in Madrid, arriving at 3am on Jan. 25, 2018. Five days later, the girl’s liver was removed and replaced with one from a deceased donor.

“She was literally almost dead before surgery,” remembers Lamjafar. But the next day, she woke up feeling immediately better, he says.

More than once, Lamjafar expresses his gratitude to Spain itself for making all of this possible. It’s clear that the worry, the days and nights of uncertainty, remain raw. He adds, in fact, that the set of tests booked by doctors in Morocco have still not been completed.

“When the doctor back home found out [that the transplant had already happened] he could hardly believe it,” Lamjafar says.

In order for transplant surgeries like this to happen, people must retrieve donor organs from deceased people. It falls to coordinator teams in hospitals across Spain to know which patients want to donate their organs in the event that they die. At La Paz, that job belongs to Belén Estébanez.

Originally from Malaga, Estébanez has been working as a transplant coordinator here for nearly four years. It’s not an easy or predictable job, she says, but it is one she describes as “a gift”.

Despite Spain having a nominal presumed consent system, in practice coordinators do all they can to find out whether a patient is happy to donate before they die, and also whether their relatives or loved ones are comfortable with this.

Around 10–15% of relatives will refuse consent, says Estébanez—a number that she would like to see fall to zero. Still, the shock of death is sometimes hard to reckon with. Estébanez remembers one patient who said he wanted to be a donor. After he died, his sister approved but his wife did not. The medical team always respects what the family wants, she says.

These conversations are never easy. Estébanez recalls one case, of a 14-month-old baby boy. He was playing in the park and started to feel unwell, so his mother brought him to a local health center. His condition worsened and he was taken to hospital. Once there, doctors confirmed he had meningitis, says Estébanez. He died shortly after.

She and her team had to ask the family if they would consent to organ donation—and also for the child to be kept on life support for 48 hours, to allow for antibiotic treatment to prevent the infection being passed on to transplant patients. As she talks, Estébanez breaks down. She wipes a tear from her cheek.

“I remember that conversation, with his mother holding her baby’s teddy bear,” she says.

On the photo ID card hanging on a lanyard around her neck, she has placed two sticky silver stars—one on the front, one on the back. Although she remembers all of the patients and families she’s worked with, these stars remind her of two particular patients who became donors after death.

One was a boy who suffered a brain injury in a bad motorbike accident. She remembers the family consenting to life support being turned off. The second star is for a colleague, a neurologist who collapsed just after meeting his son at the airport. “He suffered from a very severe brain injury and wanted to donate,” she says.

Transplant coordinators aren’t involved in the decisions about where organs will end up. That happens very nearby, however, within the walls of the National Transplant Organization (Organización Nacional de Trasplantes, or ONT). It’s here that staff communicate with the 189 hospitals in Spain that can perform organ extractions, to find out where in the country organs are available and where they are most needed. Of those 189 hospitals, 44 are able to carry out transplant surgeries.

Estébanez, like all transplant coordinators in Spain, uses a database to share information with the ONT. However, they still often rely on phone conversations too. She shows me her work phone—an old, beaten-up black plastic mobile with large buttons. It looks about 20 years old. But it does the job.

We are urgently in need of kIdney donors in Kokilaben Hospital India for the sum of

ReplyDelete$500,000,00,WhatsApp +91 8681996093

Email: hospitalcarecenter05@gmail.com